What was your trigger/inspiration for starting photography?

Accident in cahoots with necessity. I'd jacked in my job at the docks and was off on an American road-trip as a baptism for everything life cared to throw at me. Reality was in fast forward, my Doc Martens under duress. So by the time I reached the West Coast I needed a device (of sorts) to help keep track because my neuronal hard-drive had hit overload. I shot snaps of the XL vistas. I was blown away by the searing poverty. I crossed my fingers, gulped and wandered around Watts, Harlem and the Bronx, thinking, 'This isn't right...' I let it engulf me. I let it simmer up into anger and hate.

Once back in Scotland, my dad handed me a proper camera and told me to take it for a spin. My JFK moment. The blood-spatter pattern time's arrow can't reverse. Then followed the freedom of unemployment. Bus trips. A camera in one hand, a cold pie in the other. My perfect day out. And Hoi Polloi as consecration.

What do you hope to communicate/describe with your photography?

One of two things. Or both simultaneously. Sometimes I just want to lose myself, popping pearls in a carefree stream-of-consciousness. Re-enchanting my world in the hopeful hunt for tiny time-diamonds.

But usually I'm geared up for something more. I started shooting during Thatcher's dystopian skull-fuck, so my instinctive drive was towards pictures of working-class life around me. I even harbored a hair-brained idea of being a swashbuckling war photographer. But these days I wonder whether pictures of extremes (like poverty and war) can easily be dismissed as freak blips in their narrative. In which case, maybe it's more undermining to depict the pain within the commonplace. Subversion in a minor key from inside what should be capitalism's comfort zone. It's an economic model that doesn't meet many of our basic psychological needs, so however brave a face we put on it, inevitably the mask sometimes slips, revealing the stigmata of adaptation. On that understanding, my pictures tend to depict (or suggest) themes like alienation, solitude, identity and social dissonance. My tiny Trojan Horse to their Achilles heel.

Pathetic blows. If, in some phantasmagorical demi-monde, I could morph them into something with Marvel menace, they would ram a heel down on the Beast's throat. Hopefully, my intentions are worth the mileage, even if only as self-validation. Honestly, it's all worthless to me unless I can stand face-to-face with the teenage zealot who set off to discover his America and look him in the eye.

Or maybe it's just reverse alchemy. My troubled inner monologue, twisted inside-out and pixelated. My own private schadenfreude playing on repeat in a cathartic chorus. Eschatological eye-candy as leitmotiv.

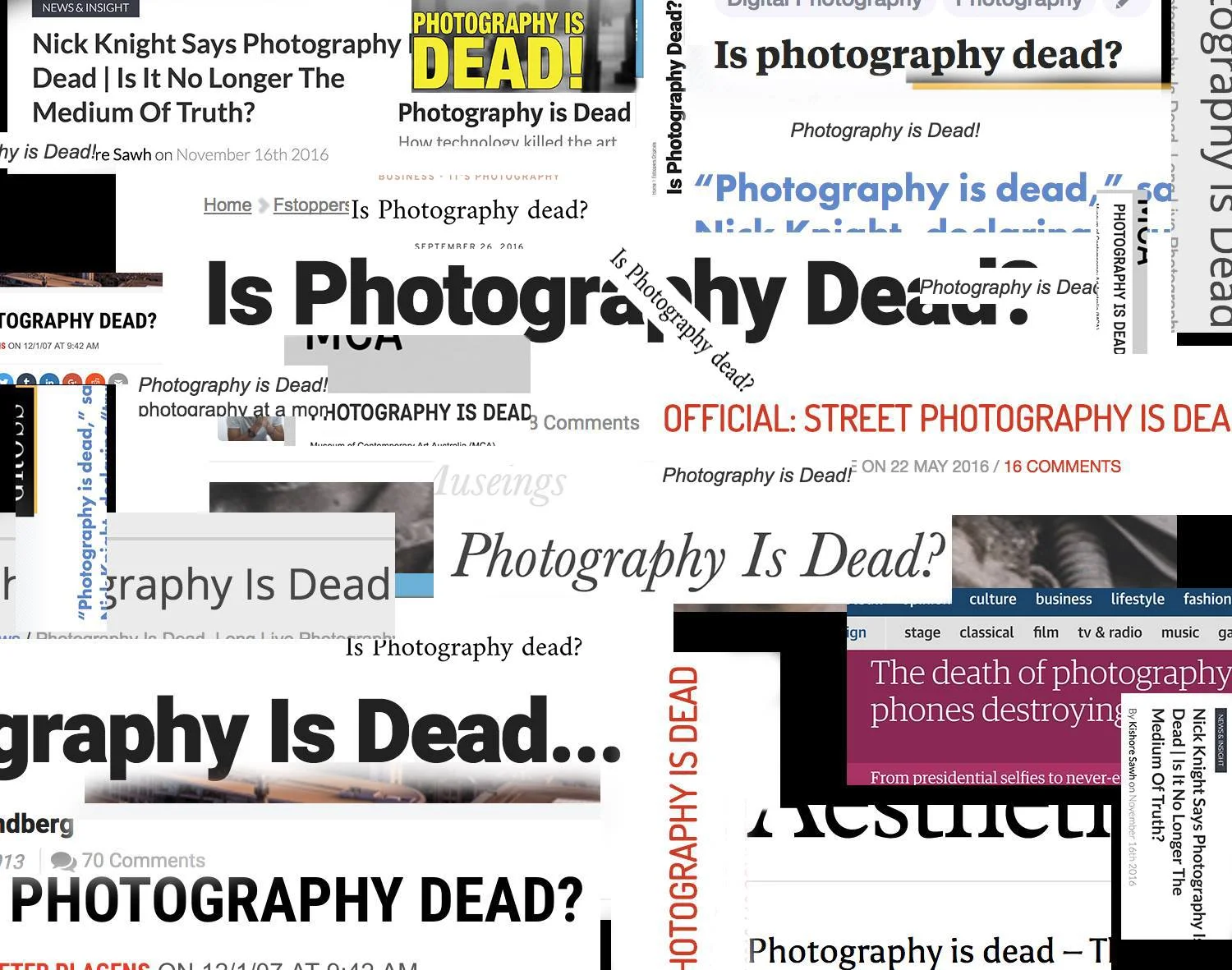

In any case, you've got to be about something, don't you? That's why I can't suffer all this burlesque shite that seems to be redefining street photography. It couldn't be more inane. It couldn't be less ambitious. A tear runs down the face of photography every time some clown adds to the pile. It's like turning up at a funeral wearing a Hawaii shirt. Philistine, flat-pack photography. Boiled-in-the-bag snapography for dizzy, miscreant fuckwits.

Harsh histrionics? Maybe. But it seems such a wasted opportunity. Almost a dereliction of duty in the sense that street photographers were once referred to as 'peace correspondents', whereas now they're increasingly more akin to court jesters. It's not funny, it's laughable. Ok, street photography is a broad church with no rules or obligations. But is it just wishful thinking to imagine a global network of street photography watchdogs? A thorn in their side. Maybe.

Has your relationship to photography changed over time? If so, how?

I think I speak for us both when I say time stood still when our eyes met. We bonded instantly, and, with her on my arm, we turned heads wherever we went. 'Platonic' wasn't in our vocabulary, and the world was our lobster. After the honeymoon years, we moved to Paris, and I foolishly assumed this would work further wonders for our relationship. But, sadly, it wasn't so, and infatuation was replaced by irritation. The toe-nail clippings, the bath soap body hair...you know the thing. Then followed a long period in which we were estranged by geography, and the relationship languished. But a few years back, a riot re-ignited our flame and, going by her blushes, I reckon I still have a place in her heart. She can be a frustrating companion, and I often feel like slamming the door on us. Until I remind myself that I probably need her more than she needs me.

What next? Maybe the first kiss will be crowned. More probably, her patience will snap and she'll drive off into the distance. Leaving me like a forlorn Jake LaMotta, scolding my own reflection in a self-referential cascade of mirrors. Ruing what might've been. A contender instead of a bum.

Six pictures and your method

Earlier on, I listed a few of my recurring themes, which maybe gave the impression of a very structured approach when, in fact, beyond commonsense planning, my photo walks are intuitive. I suppose personal themes and style are inspired by various factors - our life experience (including the knocks we took growing up), our basic attitude (our adult reaction to the world) as well as other photographers (our influences), etc. So intuition is nonetheless guided by these primal drives - meaning I do have an 'agenda' and don't sit on the fence. When I head out, I try to keep a lid on it all with a mixture of calm, concentration and stoicism. Aiming for a child-like state of curiosity. Last but not least, a catchy '45 in my head as soothing soundtrack and battle anthem.

I suppose what's fundamental to a photographer is being situation-sensitive and capable of transcribing that visually. Hearing the song of the street - receptive to it's poetry and pain. Inversely, tone-deaf photography is like watching your dad hit the dance floor after a few too many shandies...

What reels me in to a shot varies - a situation, a person, a background, etc. But in the absence of anything concrete, I seek out atmospheric conditions so I at least have one factor on my side. I don't think in terms of 'good/bad' lighting but concentrate on mood and texture instead. I don't overly fixate on the golden hour. Situation-wise, I'm looking for something pregnant with possibility or already energised. The elements that thrill me in the work of other photographers are usually beauty, social substance, emotional depth, artistic singularity and strong mood, so that's pretty much my own shopping list too.

I'm often drawn towards the use of silhouettes, shadow and reflection as I feel paradoxically they convey a richer impression of 'reality'. They've become part of my photographic lexicon. To me, they suggest elements at play beyond the fragile surface tension of appearances as well as articulating my perception of them. Pluri-dimensional. An off-kilter, spastic echo. Like that line from Lost Highway - 'I like to remember things my own way....not necessarily the way they happened'.

Is there a question we haven't asked that you'd like to answer?

Yeah. Anything that would've allowed me to spin on a sixpence and conclude this interview with a devil-may-care flourish of a reply.

You can see more of my work on my website.